When her son Pete became a star running back at Youngstown South High School, he got scholarship offers from several Mid-American Conference schools. He said he was “all set to go” to Bowling Green, until the University of Dayton, then a Division I program coached by Pete Ankney, made a late, but concerted effort to land him.

An assistant coach visited several times and that impressed Christine, especially when, in Pete’s words, the coach “guaranteed” her son would graduate from UD.

“That sold her,” Richardson said. “She wanted me to go to Dayton, to get an education, and I wanted to do what my mom wanted, so I came to UD.”

And from that commitment, both Christine and her son got more than they had dreamed.

She wanted Pete to get an undergrad degree and he not only did, but then went on and got his masters at Dayton.

He wanted to play football and he not only starred as a UD defensive back, but he became a seventh-round draft pick of the Buffalo Bills and soon was their starting safety. It was only because of a knee injury that his NFL career ended after three seasons.

But his football career was only getting started.

While in grad school at UD, he started coaching at Dunbar High School under Jack Hart and then became the Wolverines head coach.

After that he spent 14 seasons at Winston Salem State, including four as the head coach when his Rams won three Central Intercollegiate Athletic Conference titles.

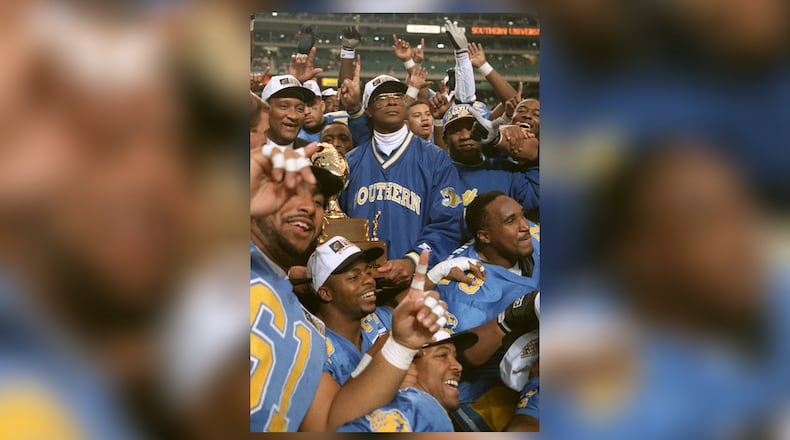

That led him to Southern University and even greater success. In 17 seasons, he guided the Jaguars to four Black National Championships, five Southwest Athletic Conference (SWAC) titles and six appearances in the Heritage Bowl.

Ten days ago Richardson was elected to the Black Football Hall of Fame, which is housed in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton.

When he’s enshrined in June, he’ll join the ranks of other fabled coaches — including Grambling’s Eddie Robinson, Florida A&M University’s Jake Gaither and Central State’s Billy Joe, who also led the programs at Cheney State and FAMU — and dozens of playing greats like Walter Payton, Jerry Rice, Deacon Jones, Ken Riley, Willie Lanier and Doug Williams.

“It’s really a tremendous honor,” he said. “When I started off coaching, I knew of some of those greats coaches and players, but I never thought I’d have the opportunity to be inducted into something where I would be alongside them.”

Appreciation for UD

When Richardson committed to UD in the mid-1960s, there were few black students on campus and not many on the football team either.

While some of the Flyers’ black players found the experience lacking back then, Richardson said he appreciates his UD days because of the education he got and the opportunities that came afterward.

“Pete roomed with our middle guard Barry Profato and that’s back in the day when whites and blacks didn’t room together,” said UD teammate Jim Place, a Flyers defensive end who went on to his own storied coaching career. “But they requested to be roommates and they lived together two years.

“Pete’s just a great guy and oh, was he a good football player!”

Richardson started out as a running back on Dayton’s 1965 team.

The following season Ankney was replaced by John McVay and Richardson became a defensive back. After going 1-8-1 in McVay’s first year, the Flyers turned things around and went 8-2 in 1966.

A big reason for the success was the Flyers’ aggressive defense, Place said:

“We had really good coaches. George Perles went on to the Steelers and Michigan State and Wayne Fontes went on to become the Detroit Lions head coach.

“And we had two great lockdown corners with Pete and Theron Sumpter.

“We played man on every play because our two corners locked up the other team’s receivers. Coach Perles had us stunt 90 percent of the time and that allowed us to wreak havoc because Pete and Sumpter had the receivers locked down and the quarterback was just standing there for several seconds with nowhere to throw.”

Place said Richardson didn’t just have skill, he has some swagger,

“Here’s one story,” Place said with a laugh. “I was a sophomore and Pete was a year older, so we played varsity together two years.

“I remember we went down to play UC (in 1966) and we were huge underdogs, but we beat them pretty good (23-7).

“They had a running back named Clem Turner, who was all-everything in Ohio. He had been the MVP of the North South All Star Game (and later played with the Cincinnati Bengals, Denver Broncos and in the Canadian and World Football leagues.)

“He was going to bring UC back to greatness.

“I was fortunate in that game and got a real good lick on him. But just as I was getting up, Pete came over the top of him and started trash talking him. Pete followed him the whole way back to the huddle trash talking him.

“On the next play, (Turner) comes out and screams at me: ‘I’m gonna get you!’

“I thought, ‘Why get me? Pete’s the one talking to you!’”

Richardson gave the Flyers a little edge and they used it.

The defense was ranked 20th in the nation, allowing just 10.8 points per game. The team beat Louisville, Ohio University, Toledo, Xavier, Buffalo, Richmond and Northern Michigan, but a late season loss to Miami knocked them out of a bowl game, which, in those days were a lot harder to get into than now.

While Dayton was not a pipeline to the NFL and Richardson said he had no pro dreams for himself at first, the concept wasn’t completely foreign to him.

“I had two cousins — Bill and Melvin Triplett — who played professional football.

Mel came out of the University of Toledo and played eight seasons with Minnesota and the New York Giants, where a young Lew Alcindor idolized him and chose to wear his No. 33 on the basketball court.

Bill Triplett was a 1,418-yard rusher at Miami University in 1961 and played 10 seasons in the NFL with St. Louis, the Giants and the Detroit Lions.

Once Richardson became a pro, he showed his scrappy side plenty, Place laughed:

“It seemed liked he was always covering the tight ends and he’d get into it with guys like John Mackey. He made a lot of highlight reels with his fisticuffs.”

In 39 NFL games — 25 as a starter — he had eight interceptions and five fumble recoveries. And that included playing his third year with a knee injury he suffered in the preseason.

“He was the real deal” Place said. “When you’ve played with a guy and then he plays in the NFL, you follow him. I remember as a you guy watching him on TV and saying, ‘Man, I played with that guy!’”

The two stayed in touch over the years — meeting for lunch at national coaching conventions — and Place especially followed the way his old teammate changed the fortunes of the Southern program he took over in 1993.

The Jaguars had had three straight losing seasons before Richardson got there and when he took over he instilled a sense of discipline — more time in film study, less time with girlfriends — and at first the players, especially upper classmen, bristled.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

As Mike Gegenheimer wrote in a 2018 story about Richardson that appeared in the Baton Rouge Advocate:

“In his annual speech to freshman on the first day of practice, Richardson would say: ‘You’re here to get an education and play football. You don’t need to worry about Susie Q. back home because she’s with Jody now.’

“His entire demeanor was off-putting.”

Soon though his discipline paid big dividends and eventually the players came around.

That first year his team went 11-1 and won the black college football national championship, a title the Jaguars claimed again in 1995, 1997 and 2003.

“It was always fun watching Pete’s team play that big game against Grambling each year,” Place said.

The rivalry game — called the Bayou Classic — would draw 50,000 to 70,000 people to the Superdome in New Orleans. Richardson’s teams won the first eight matchups after he took over — he went 5-0 against Eddie Robinson — and won 12 of the 17 Classics his team played in.,

“I liked coaching because of the relationships you could build with the players,” Richardson said. “A lot of them hadn’t come from a lot and once I walked in those same shoes. Someone helped me along the way and I wanted to do the same for them.

“It’s rewarding to see them succeed and develop, especially when you see them later in their lives with their families and they are doing well.”

“Glad I get to share it’

Richardson, who had just two losing seasons at Southern in 17 years and went 134-62 overall, was fired in 2009 after the Jaguars went 6-5.

It took a while for him to get over his dismissal from the program he built into such prominence, but he’s since been enshrined in the Southern Hall of Fame — the Louisiana and Winston Salem State halls of fame, too — and he now does color commentary for the radio broadcasts of Jaguar games.

He still lives in Baton Rouge, La., but his wife Lillian passed away three years ago.

His only child, daughter Deborale, lives in Cleveland with her family and Pete’s now visiting them for Christmas.

“I’m glad I got his honor while I’m still living,” he said. “Lot of times these kinds of things come around after he person is gone. But I’m glad I get to share it with my daughter and grandkids.

As for his late mother, he admitted he didn’t always do what she wanted.

“When I was a young boy, I was very small,” he said. “She didn’t even want me to play Pop Warner. She thought I was too small for football.”

He played anyway.

It turned out to be a Hall of Fame decision.

About the Author